Siavash Monfared

Siavash Khosh Sokhan Monfared

Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen

previously: Harvard University, California Institute of Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and University of Oklahoma

Email

Google Scholar

GitHub

Research

Projects

Publications

Mentorship

06/19/2025

Our paper on “Force transmission is a master regulator of mechanical cell competition”, Nature Materials, 2025. [link] wins the ‘Les Grandes Avancées en Biologie’ from French Académie des sciences!

03/14/2025

Cell competition maintains tissue health through the elimination of cellular sub-populations with reduced fitness. Despite the importance of cell competition in various physiological and pathological mechanisms, our understanding of the physical mechanisms arming a sub-population with more fitness remains limited. Particularly elusive is the role of intercellular forces which stems from the absence of tools to simultaneously control intercellular force transmission capabilities and measure the key physical properties that govern cell competition. By combining in-vitro experiments with in-silico modeling, our study challenges the common belief that winning cells always expel others through squeezing. In this study, we show that cells can remain compressed and still emerge as winners by unraveling the functional basis of a novel mechanism due to force transmission capability of the competing cells. The discovery of this physical mechanism has overarching implications in most vital biological processes, including morphogenesis as well as diseases such as acute inflammation and cancer.

Reference:

- A. Schoenit (1st co-author), S. Monfared (1st co-author), L. Anger (1st co-author), C. Rosse, V. Venkatesh, L. Balasubramaniam, E. Marangoni, P. Chavrier, R.-M., Mège, A. Doostmohammadi, B. Ladoux. “Force transmission is a master regulator of mechanical cell competition”, Nature Materials, 2025. [link]

03/07/2025

The development of complex multicellular organisms from a single parent cell is a highly orchestrated process that cells conduct collectively without central guidance, creating intricate dynamic patterns essential for development and regeneration. Despite significant advances in imaging spatiotemporal dynamics of cell collectives and mechanical characterization techniques, the role of physical forces in biological functions remains poorly understood. Physics-based models are crucial in complementing experiments, providing high-resolution spatiotemporal fields in three dimensions. This review focuses on dense, soft multicellular systems, such as tissues, where mechanical deformation of one cell necessitates the re-organization of neighboring cells. The multi-phase-field model offers a rich physics-based framework to advance our understanding of biological systems and provides a robust playground for non-equilibrium physics of active matter. We discuss the foundational aspects of the multi-phase-field model and their applications in understanding physics of active matter. We also explore the integration of biological physics with experimental data, covering cell migration, heterogeneous cell populations, and confined systems. Finally, we highlight current trends, the importance of multi-phase-field models in biological and physics research, and future challenges.

Reference:

- S. Monfared, A. Ardaševa, A. Doostmohammadi, “Multi-phase-field Models of Biological Tissues”, arXiv, 2025. [link]

01/08/2025

This manuscript presents a novel connection between stress transmission capability modulated via reduced cell-cell adhesion and changes in the mode of cell extrusion, i.e. live vs dead. It shows that weakened E-cadherin expression, commonly observed in various tumors, leads to increased live cell extrusion and a greater proportion of basal extrusion in MDCK cells, cysts, and tumors. In contrast, apoptotic extrusion in wild-type cells corresponds to heightened compressive stress and fluctuations, which occur before caspase activation and apical extrusion. This link is validated through stress measurements and modeled effectively using a multi-phase fields model. Since cell extrusion is essential for maintaining tissue homeostasis and size, understanding the direction of extrusion (apical vs. basal) can reveal critical insights into tissue health and invasion. This study highlights how stress, adhesion, and cell stiffness influence both extrusion direction and the balance between live and apoptotic extrusions.

Reference:

- L. Balasubramaniam (1st co-author), S. Monfared (1st co-author), A. Ardaševa, C. Rosse, A. Schoenit, T. Dang, C. Maric, L. Kocgozlu, S. Dubey, E. Marangoni, B.L., Doss, P. Chavrier, R.-M., Mège, A. Doostmohammadi, B. Ladoux, “Dynamic forces shape the survival fate of eliminated cells”, Nature Physics, 2025. [link]

05/08/2024

Our study is one of the first on spatial correlation and organization of stress chains in dense, squishy active matter. An intriguing outcome of our research is the encoding of mechanical information in the studied stress chains, given that distinct underlying mechanisms for different control parameters manifests in a similar stress scaling near the solid-to-liquid transition. We expect these results to be of wide interest in the physics, mathematics, and biology communities.

Reference:

- S. Monfared, G. Ravichandran, J.E., Andrade, A. Doostmohammadi, “Short-range correlation of stress chains near solid-to-liquid transition in active monolayers”, The Journal of Royal Society Interface, 21:20240022, 2024. [link].

01/05/2024

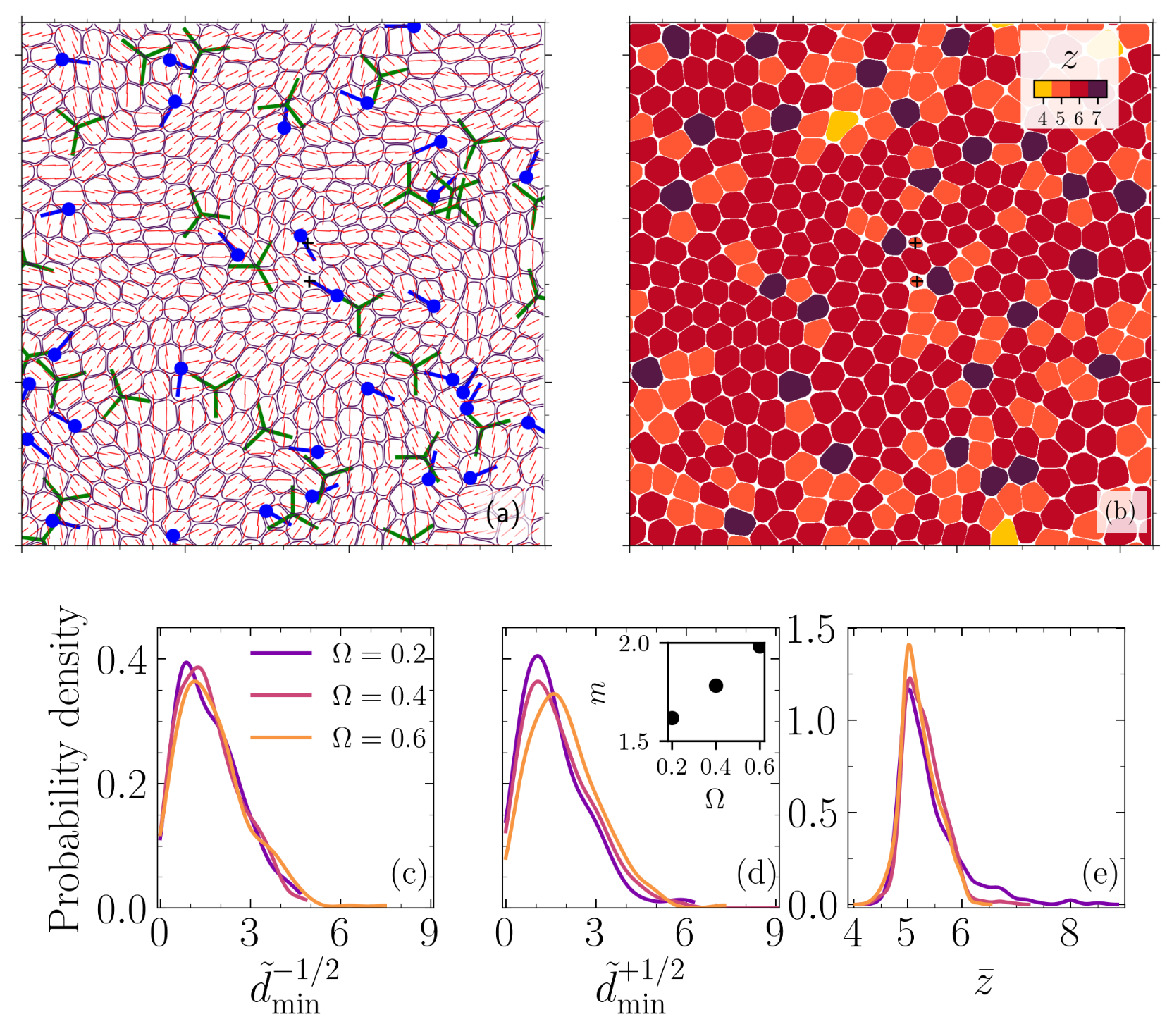

Although the expanding nature of cellular systems is central to their biological functions, the majority of approaches to study this topic are constrained to systems that conserve volume and/or mass and focus on active force generation due to cell motility. This latest development allows us to study active force generation due to proliferation, relaxing conservation of mass/volume. Proliferation in soft, dense living matter necessitates deformation and re-organization that can create a feedback loop (with the source of expansion) crucial to developement and regernation. Altought this entry does not correspond to a new publication, but this is my current focus and I thought the simulation looks cool! hope you enjoy it too.

04/24/2023

Eliminating unwanted or excess cells is a matter of life and death for the cell layers covering surfaces of our bodies. Nevertheless, since all the existing studies have only focused on effective two dimensional models of the cell layers so far, fundamental questions about the three-dimensional phenomenon of cell extrusion and in particular physical forces involved in the process remain unanswered.

By developing a three-dimensional model and large scale simulations and in an analogy with liquid crystals, a state of matter between a solid and isotropic liquid , we show that cells can switch between distinct mechanical pathways – leveraging defects in nematic and hexatic orders – to eliminate unwanted cells (nematic and hexatic orders are manifestations of two different types of rotational symmetry in liquid crystals). Our findings provide a unique perspective on how through collective self-organization, cells exploit mechanical and physical constraints to switch between different modes of cell elimination.

Press coverage: Caltech News, Phys.org.

Reference:

- S. Monfared, G. Ravichandran, J.E., Andrade, A. Doostmohammadi, “Mechanical basis and topological routes to cell elimination”, eLife, 12:e82435,2023 [link].

10/14/2022

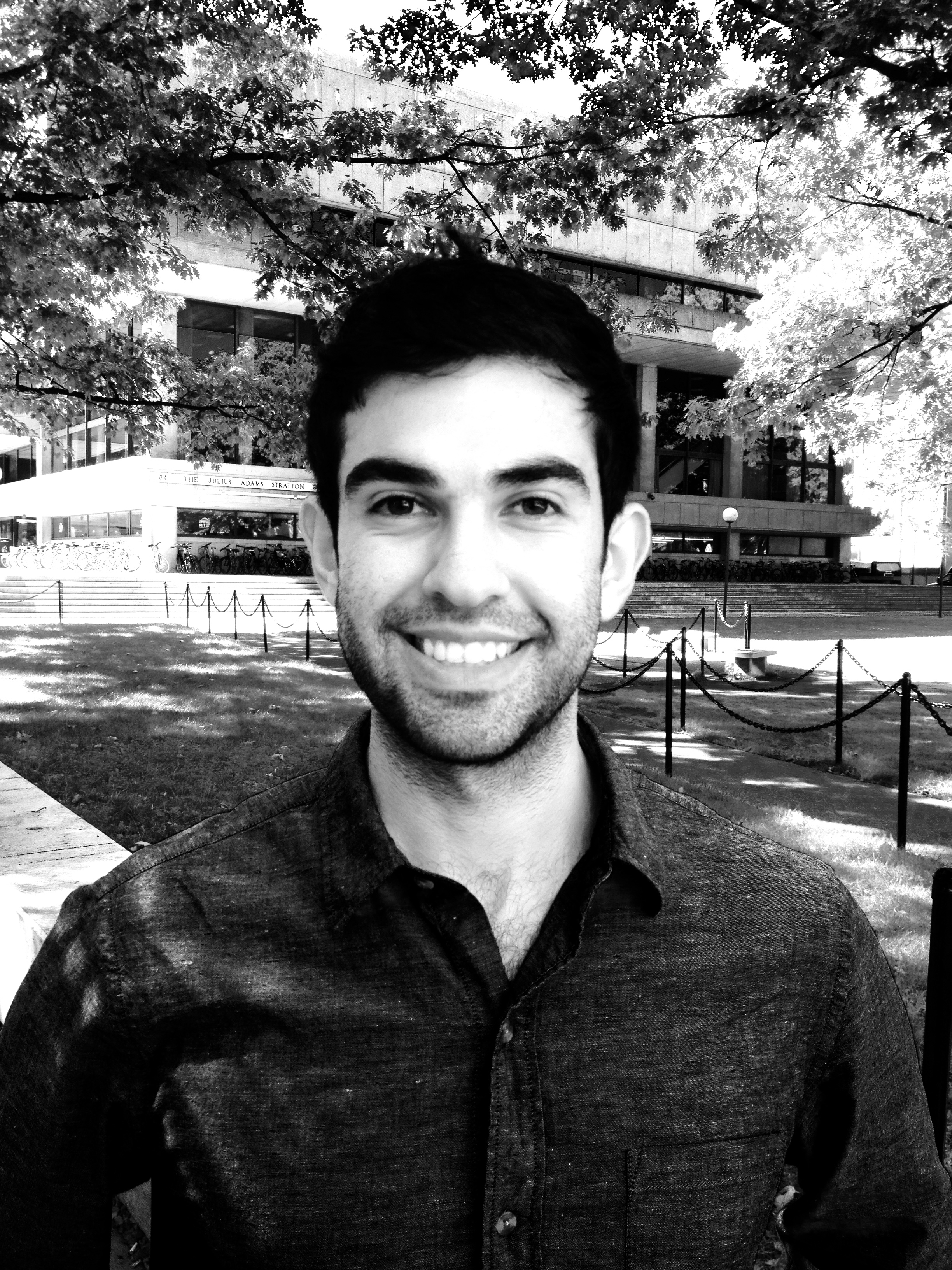

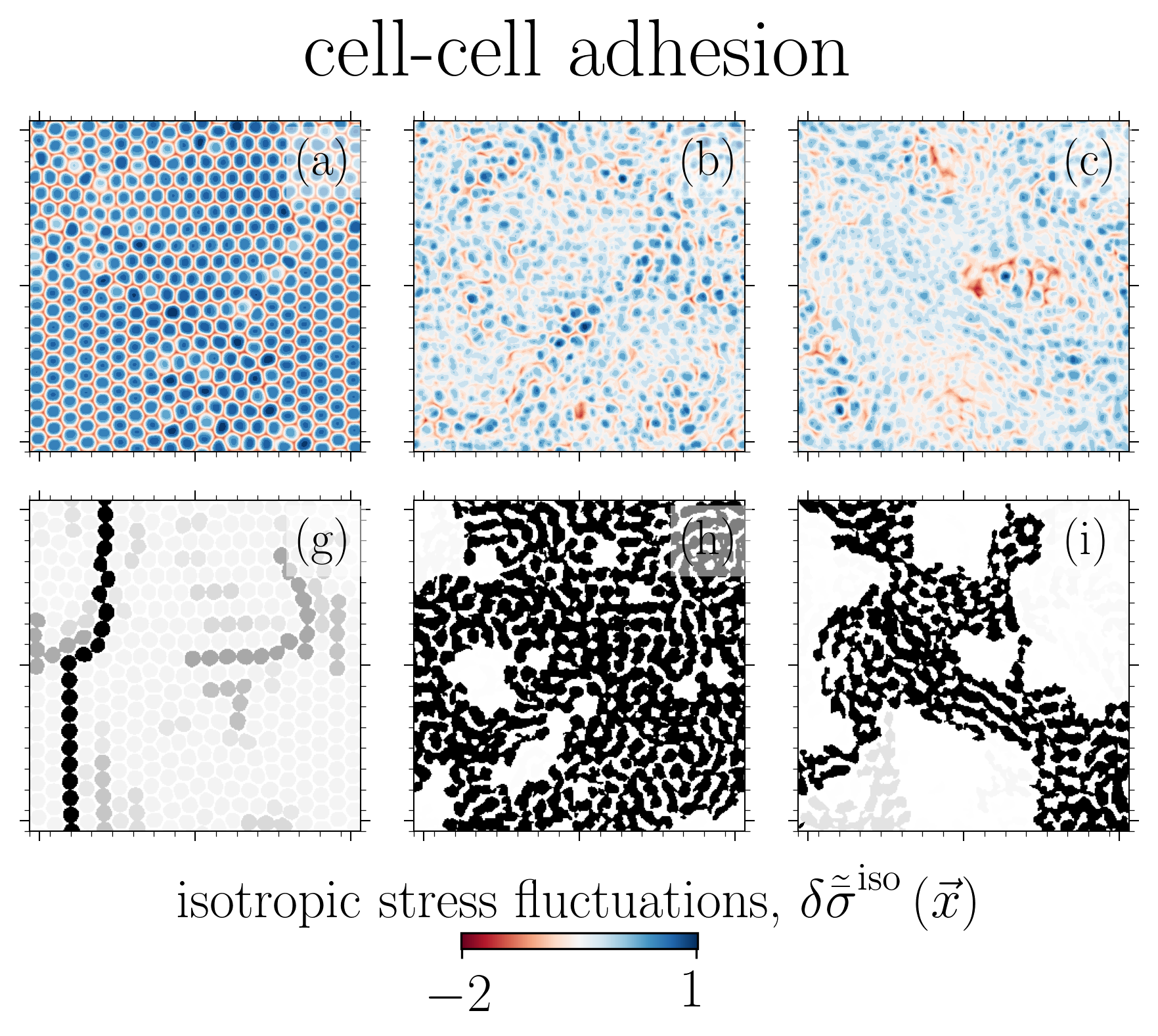

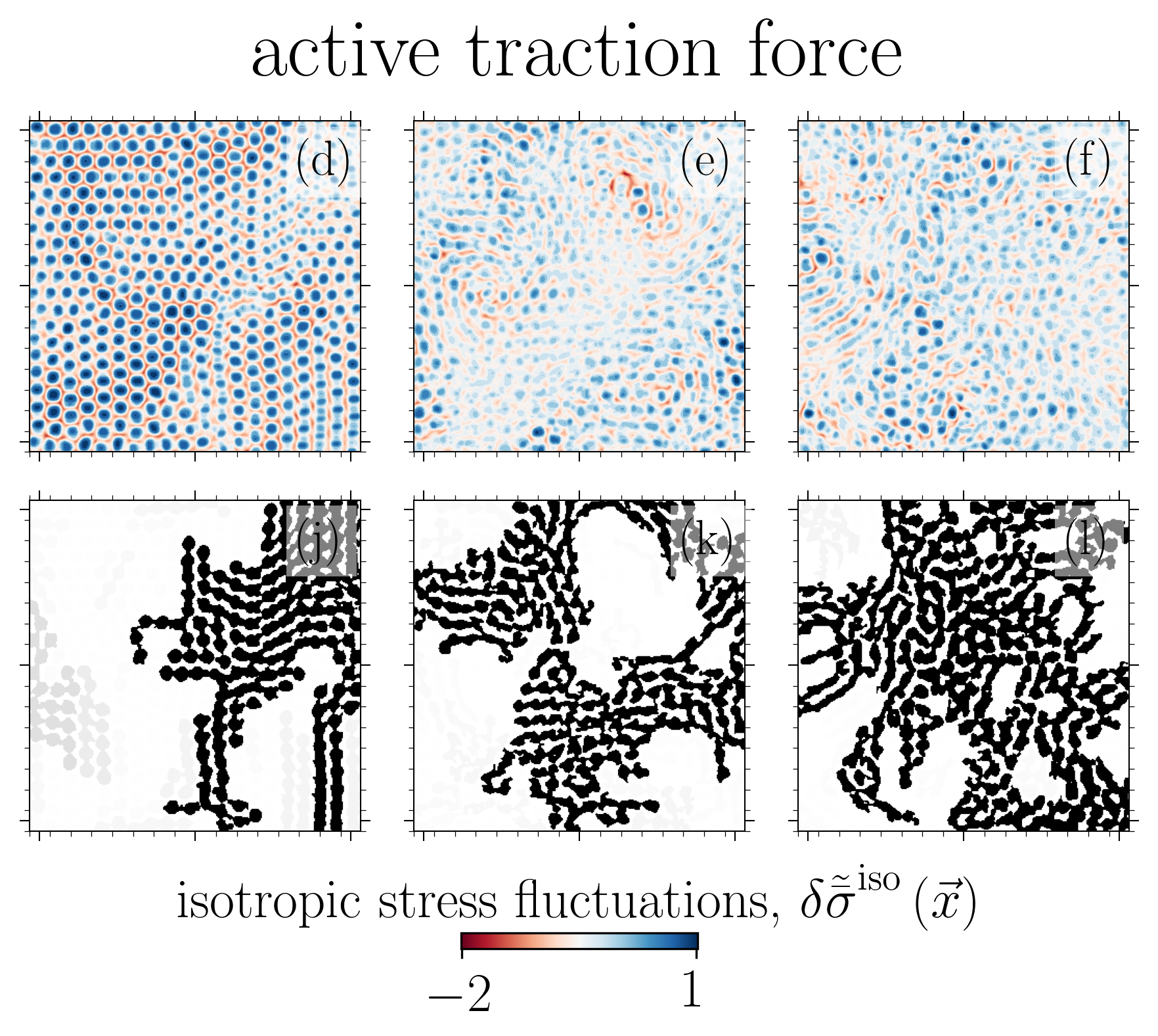

The solid (glass-like) to liquid phase transition in cellular systems is relevant to a range of biological processes including cancer metastasis, wound healing and tissue morphogenesis. However, our fundamental understanding of how cells collectively switch between these two states remains limited. Using two distinct paths to model this transition based on (i) cell-cell adhesion and (ii) active traction, we link this phase transition to the emergent isotropic stress patterns and their percolation in active cell layers. For each path, we map this phase transition onto the 2D site percolation universality class. This study offers a new perspective on the fundamental mechanical mechanisms associated with the criticality of glass to liquid transition in active cell layers.

Reference:

- S. Monfared, G. Ravichandran, J.E., Andrade, A. Doostmohammadi, “Stress percolation criticality of glass to fluid transition in active cell layers”, arXiv:2210.08112, 2022. [link][pdf].

08/10/2021

Our work is the first to map and reveal the importance of 3D out-of-plane stresses in cellular layers. Moreover, our findings on the distinct roles of topological defects and disclinations provide a unique perspective on how through collective self-organization, cells exploit mechanical and physical constraints to switch between different modes of cell elimination. Additionally, the framework presented herein allows for independent tuning of cell-cell and cell-substrate interaction forces, that is unprecedented in studying collective cell behavior and as such is expected to open the door to a new set of questions in mechanobiology.

The results contribute to the increasing realization of the importance of the mechanical properties of cells in controlling their behavior, and we hope that they will be of interest to a broad range of mathematicians, biophysicists and cell biologists interested in connecting the physics of cellular self-organization to the dynamics of biological systems.

Reference:

- S. Monfared, G. Ravichandran, J.E., Andrade, A. Doostmohammadi, “Mechanics of live cell elimination”, arXiv:2108.07657, [link][pdf].

12/15/2020

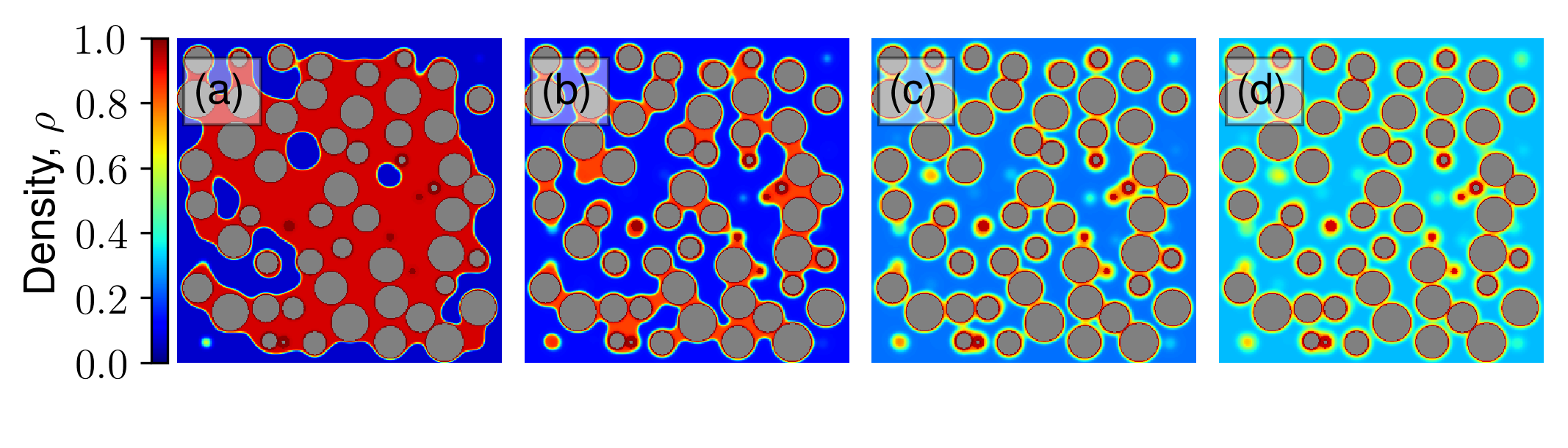

This paper advances understanding on confined fluid behavior in (dis)ordered granular aggregates and their inverse porous structures. For the first time, we unravel the link between surface-surface correlations to the degree of confinement while addressing long-standing questions on the first-order nature of liquid-gas phase transition and whether capillary critical temperature represents a true critical temperature. This is done via access to capillary pressure fields and a finite size scaling analysis that maps the studied systems onto the Random Field Ising Model universality class as conjectured by F. Brochard and P.G. de Gennes. We link the underlying random fields to disorder in local fluid-solid interactions.

These findings have significance for both applied fields, such as pore size characterization and carbon capture, to theoretical fields, including glass physics, wet granular physics and physics of confined fluids.

Reference:

- S. Monfared, T. Zhou, J.E., Andrade, K. Ioannidou, F. Radjai, F.-J. Ulm, R. J.-M. Pellenq, “Effect of confinement on capillary phase transition in granular aggregates”, Physical Review Letters, 125, 255501, 2020. [link][pdf].